Translations are tricky. Words and phrases and ideas don’t always translate cleanly and directly from one language into another, especially word for word.

Mistranslations can be funny. And sometimes embarrassing. And, unfortunately, sometimes tragic.

Take the super catchy blog post title above: “bite the wax tadpole”.

That phrase is a mistranslation of “Coca Cola” into a Chinese dialect. “Coca Cola” = “Ke-Kou-Ke-La”, which unfortunately for the Coca Cola Company, can either mean “female horse stuffed with wax” or “bite the wax tadpole” (my fave) depending on the dialect.

Yes, I’ll have a diet female horse stuffed with wax, please! No ice!

There’s actually more to the Coca Cola story here: CLICK HERE

In the spirit of giving equal time to competitors, Pepsi had a translation problem in China, too.

The marketing phrase “Come alive with Pepsi!” translated into “Pepsi brings your ancestors back from the dead!” in China.

Now, Pepsi may have some seemingly miraculous benefits for the drinker, but resurrection of ancestors isn’t one of them.

(Note: Snopes.com says this may or not have actually been true, but either way, it makes a great story!)

Back in the 1950s, Pepsodent toothpaste had an advertising slogan that said, “You’ll wonder where the yellow went when you brush your teeth with Pepsodent!” That slogan worked great in America because we value white teeth as a sign of good health and grooming.

However, when Pepsodent entered the Southeast Asian market using the same ad campaign, it didn’t go so well. What Pepsodent didn’t understand was that in many regions in Southeast Asia, like Vietnam, Indonesia, and some parts of the Philippines, it was a tradition among members of different tribes to blacken their teeth because they believe that it enhances their sex appeal.

Oh.

So Pepsodent had a problem, not because of mistranslation, but because of a lack of cultural research, assuming that what worked for Americans would also work in Southeast Asia.

It didn’t.

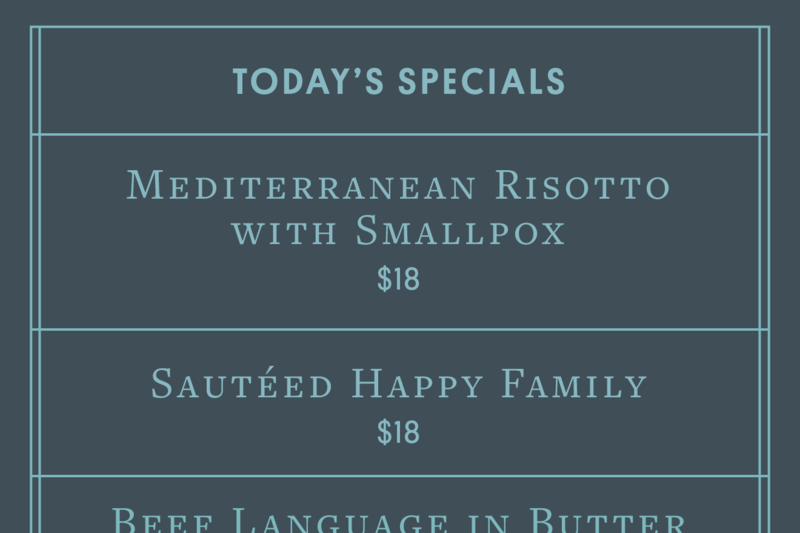

Here are some more fun mistranslation examples:

Seen on a sign in a Norwegian cocktail lounge: “Women are requested to not have children in the bar”. That is some good advice all the way around, I’d say.

On a sign in a New Zealand restaurant window: “Open 7 days a week, and weekends too”! Awesome!

In an Italian cemetery: “Persons are prohibited from picking flowers from any but their own graves.” Rules are rules…

In a Copenhagen airline ticket office: “We take your bags and send them in all directions”! At least they admit it.

Outside a Hong Kong tailor’s shop: “Women may have a fit upstairs”. Excuse me, but we’ll have our fits wherever we feel like it, thank you very much!

From a car rental brochure in Tokyo: “When passenger of foot heave in sight, tootle the horn. Trumpet him melodiously at first, but if he still obstacles your passage then tootle him with vigor.” I think I can trumpet him, but I’m not so sure about tootling…

Doctor’s office in Rome: “Specialist in women and other diseases”! I’m not quite sure how to take that.

Sign at a disco in Mexico: “Members and Non-members only.” So, we can go in, then?

A sign advertising donkey rides in Thailand: “Would you like to ride your own ass?” Um, noooo…

At a barber shop in Tanzania: “Gentlemen’s throats cut with nice, sharp razors.” At least it’ll be quick…

Sign on a Romanian elevator: “The lift is being fixed for the next day. During that time we regret that you will be unbearable.” I’m pretty much always unbearable…

From a Serbian elevator: “To move the cabin, push button for wishing floor. If the cabin should enter more persons, each one should press a number of wishing floor. Driving is then going alphabetically by national order.” Hooray!! Wishing floors ARE real!

At a restaurant in Mexico: “Special today – no ice cream”. That’s not very special, Mexico.

From a Canary Islands hotel: “If you telephone for room service, you will get the answer you deserve.” That’s harsh…

From a hotel in Turkey: “Flying water in all rooms. You may bask in sun on deck.” It IS hot in Turkey in the summer, but still…

Those are fun aren’t they? I think we’d all agree that some mistranslations can be simply hilarious, and provide a good laugh.

No harm done, right?

Translating from one language to another is really difficult for a number of reasons. It’s a skill that people work hard to develop, but it can still trip up even the professionals. You’d think the government would be pretty good at this, right? Well…

When President Jimmy Carter traveled to Poland in 1977, the State Department hired a Russian interpreter who knew Polish, but was not used to interpreting professionally in that language. Carter’s statement “when I left the United States…” was translated through the interpreter as “when I abandoned the United States”, and “your desires for the future” were mistranslated as “your lusts for the future”. The meanings were close, but not accurate. The media in both countries very much enjoyed these translation mishaps.

A bit embarrassing, but again, no real harm done.

How about this one?

Eusebius Hieronymus Sophronius, thankfully known as Jerome (347 – 420 AD), was probably the greatest Christian scholar in the world by his mid-30s. Jerome spent three decades translating the Bible from its original Hebrew text (instead of the using the Greek translation as his source) into a Latin version that would be the standard – known as the Vulgate – for more than a millennium. His translation became the basis for hundreds of subsequent translations.

So far, so good.

But he made a pretty famous mistake in that arduous translation project. When Moses comes down from Mount Sinai (in the book of Exodus) the text says that his head had “radiance” or, in Hebrew, “karan.” But Hebrew is written without the vowels, and Jerome had read “karan” as “keren,” which translates to English as “horned.”

From this error came centuries of paintings and sculptures of Moses with horns and the odd offensive stereotype of the horned Jew.

Even though the original text didn’t really say “horned” Moses, I can bet you that those who had read that he was “horned” their entire life with their favorite translation argued strongly that it DID mean “horned”.

Even though it didn’t.

Jerome said many wise things, such as “It is worse still to be ignorant of your ignorance.”

The more you know.

Can you see how one simple, easy to confuse mistake can totally hijack the meaning, adding to or taking from the original intent?

It’s a wonder we get anything right!

Here’s a mistranslation that had devastating consequences for the entire world.

The United States’ National Security Agency declassified a World War II document which points to what is likely to be the worst translation mistake in history. Although we can only guess at what the world would be like without this error, it is very likely that the sad fate of Hiroshima has been the result of a huge mistake in Japanese to English translation.

The story is as follows: in July 1945, the allied countries meeting in Potsdam submitted a harshly -worded declaration of surrender terms. After their terms were translated from English into Japanese, the Allies waited anxiously for the Japanese reply from the then Japanese Prime Minister, Kantaro Suzuki. This ultimatum demanded the unconditional surrender of Japan. The terms included a statement to the effect that any negative answer from Japan would invite “prompt and utter destruction.”

Meanwhile, newspaper reporters were pressuring Prime Minister Suzuki in Tokyo to say something about Japan’s decision. No formal decision had been reached, and therefore Suzuki, falling back on the politician’s old standby answer to reporters, replied that he was “withholding comment”. The Japanese Prime Minister stated he “refrained from comments at the moment.”

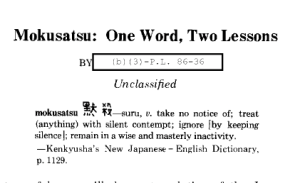

Mokusatsu was the key word to express his idea, a word that can be interpreted in several different ways but that is derived from the Japanese term for “silence”.

As can be seen from the dictionary entry above, the word can have other quite different meanings from those intended by Suzuki, but the Japanese to English translation conveyed just one meaning.

Media agencies and American translators interpreted Mokusatsu as “treat with silent contempt” or “take into account” (in other words, “to ignore”), as the categorical rejection by the Japanese Prime Minister. The Americans understood that there would never be a diplomatic end to the war and were naturally annoyed by what they considered the arrogant tone used in the Japanese translation of the Prime Minister’s response. International news agencies reported to the world that in the eyes of the Japanese government the ultimatum was “not worthy of comment.”

Mokusatsu, a word that we could very well translate as “no comment” nowadays, or “let me withhold comments for now” was translated as “let’s ignore it”.

The atomic bomb was launched on Hiroshima 10 days later. A translation error may have led to the death of more than 70,000 people instantaneously, and some 100,000 as a result of the destruction and radiation. Whoever it was who decided to translate mokusatsu by the one meaning and didn’t add a note that the word might also mean nothing stronger than “to withhold comment” did a horrible disservice to the people who read his translation, people who knew no Japanese, people who would probably never see the original Japanese text and who would never know that there was an ambiguous word used. Other points of view, however, point fingers at the Prime Minister himself for using such an ambiguous term.

A copy of the declassified document can be downloaded from the link to the American NSA. Source: https://www.pangeanic.com/knowledge_center/the-worst-translation-mistake-in-history/

Things got real all of a sudden didn’t they?

Word for word translations don’t work very well if you are trying to really understand the true meaning of what is being communicated, especially in a different culture. You might get the gist. Or you might become even more confused. Some things just don’t translate from one language/culture to another directly.

We have deep feelings about food. Think about our phrases “comfort food” and “home cooking”. The meaning and the feelings associated with those phrases go way beyond saying “mashed potatoes” or “fried chicken” or “birthday cake”. Other cultures may not understand exactly what we mean because they don’t experience the same feelings associated with words and phrases as we do.

And vice versa.

Cubans love ropa vieja, a shredded beef dish whose name, literally, translates to “old clothes”.

Mexicans enjoy tacos sudados, which translated directly to English, means “sweaty tacos”.

Moroccans love roasted sheep head – me, not so much.

In Croatia, bitter flavors are valued, while in other countries, calling a dish or drink “bitter” would be an insult.

“Nuts of jack” anyone? That is actually a French-to-English mistranslation of scallops.

How about some Maultaschen, which translates from German to English as “mouth bags” but is really a dumpling or ravioli type dish.

You can run into translation confusion even if you are speaking the same language, during the same time period, but in different cultures. Take American English versus British English for example:

So why do I care about all of this, you might ask?

I mean, it IS fascinating to study this kind of thing. And I do like food.

But, I care because these same types of translation and interpretation challenges occur with Biblical translations too, not just in advertising campaigns or funny restaurant signs, or more tragically, wartime communications that have devastating impacts.

And mistranslations of Biblical truths impact all of us.

You saw just how difficult it can be to properly translate from one language to another even when we are living in the same time period and using professional translators. Imagine the enormous difficulty in translating to modern language and usage and cultural meaning from an ancient language and culture written a few thousand years ago.

Even under the best of circumstances, one can’t completely remove cultural influence and subjectivity from their efforts.

I care what message God truly intended to send to humans through his prophets and inspired writers, into what we have compiled into the Bible.

But, I understand that humans have a propensity to mess things up, sometimes with the best of intentions, and sometimes with ulterior motives. I understand that Satan is at work too, trying to confuse us and mislead us so that we are as inefficient, frustrated, and discouraged as we can possibly be.

It matters to me.

When you know better, you do better. Or you/we/I should anyway.

I think we all want “accuracy” when we are looking for a Bible translation. But the definition of “accuracy” varies: do you mean word for word? Or thought for thought? Or overall message? Those are all legitimate pieces of the translation puzzle, but you probably can’t have absolute accuracy and satisfy all 3. Because the languages and times and culture are so DIFFERENT.

All these things must be taken into consideration when trying to determine what the original writers of scripture intended to communicate:

- The words they used (of course)

- Their audience

- Their reason for writing what they wrote

- The context

- The culture to which it was written

- Consistency with other messages (passages, letters) written by the author

Some of that is realllllllly difficult to figure out.

We also need to be sure we are searching for truth, not just comfort or status quo. If truth is our common goal, then considering other ways of understanding what these writers wrote long ago should not be threatening to us.

The hard part is that smart, well-studied, well-intentioned, sincere people will still disagree on what criteria to use for “accuracy” and what the words/phrases mean to us now.

Another challenge is that people feel very strongly about religion, and become emotionally tied to their opinions, even to the point of moralizing them. Moralizing simply means that a person feels so strongly about their views/opinions that they basically make a law and expect others to see things the same way. Sometimes people don’t even know that that’s what they’re doing. We actually do this all the time.

Plus, change is hard. Most folks don’t want to go looking for change when they are perfectly comfortable with the status quo.

Think about Jerome, the bible translator again. I can just hear his contemporaries saying, “Leave it alone, Jerome! Why are you always stirring things up?? We don’t need a Hebrew to Latin translation! We’ve always used the Greek source! It means what it says, Jerome!”

What if Jerome had just given up because the push-back was too intense?

I want to understand more deeply what certain difficult-to-interpret passages really meant, what the author intended to convey, not just blindly follow what I’ve been told all my life that they mean.

Perhaps those passages DO mean what I’ve been told all my life.

But perhaps they do not. And if they don’t, shouldn’t we know that? Don’t we want to know what was meant and not just what we are comfortable with?

If they do not mean what we have thought they mean, isn’t it worth the work and the time and the discomfort and the uncertainty and the fear to study that?

The idea of searching scripture deeply and being able to determine truth is very Biblical:

Acts 17:11 ESV: “Now these Jews were more noble than those in Thessalonica; they received the word with all eagerness, examining the Scriptures daily to see if these things were so.”

2 Timothy 2:15 NIV: “Do your best to present yourself to God as one approved, a worker who does not need to be ashamed and who correctly handles the word of truth.”

Or if you prefer, the KJV: “Study to shew thyself approved unto God, a workman that needeth not to be ashamed, rightly dividing the word of truth.”

If passages are studied – really studied, with as objective a mind as possible – and we end up back at the place we started – that’s great! We will have studied and can feel confident in our understanding, even if we don’t particularly like the conclusion.

We might get to the end of the study and find out that people still come to different conclusions. All valid. That happens quite often.

But if we study and end up with a different outcome – that may be scary, and weird, and may stir the pot up a good bit, and we might not know exactly what we want to do with this deeper understanding, but I have it on good authority that the truth will set us free.

John 8:31-32: “31 To the Jews who had believed him, Jesus said, “If you hold to my teaching, you are really my disciples. 32 Then you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.”

Jesus was speaking to those who were already believers here. “Holding to His teaching” implies that they had to know what His teaching actually said. Only then, would it set them free.

Going back to my recent blog posts that dealt with being a good listener and dealing with conflict:

Conflict Resolution Skills Link

If you’ll remember, I shared that the first and most important goal in communication and conflict resolution is to LISTEN and UNDERSTAND. Otherwise, you don’t have enough information to make an informed decision. If you don’t know what logic led someone to arrive at an opinion that is diametrically opposed to yours, you won’t be able to have any kind of profitable discussion about it. “So and so said” and “but this is what we’ve always done” or “well, my way is the right way” isn’t gonna cut it if you want to resolve an issue or understand each other.

Sincere people can be sincerely wrong, myself included.

Translation accuracy is important.

I’m ready to understand more deeply.

It matters.