We love sayings, don’t we?

You’ve probably heard these sayings before:

- Children should be seen and not heard!

- The only thing to fear is fear itself!

- If people were meant to fly, they’d have wings!

- The earth is flat!

- You’ll never need more than 640K of RAM!

When those phrases were first used, the people who said them were dead serious. They were said based on the time, culture, and knowledge of the day. But now, those same sayings seem humorous, and even a bit silly to us.

In school, we learn early on to use context clues to help us understand the meaning of words and to solve problems that the text addresses.

For example, take the word “bat”.

When used as a noun, “bat” could mean a long wooden or aluminum club that baseball players use to hit a baseball. Or it could refer to a flying mammal.

If it’s used as a verb, it could mean to toss something (either an object or an idea) around.

The only way you’ll know which meaning the author intended is to read the surrounding text and place that word into context. Otherwise, you’re just guessing.

The word “context” was first used in 1568 and meant “the weaving together of words”.

The word originates from Latin contextus (connection of words, coherence), from contexere (to weave together), from com- + texere to weave.

The definition of “context” today: the parts of a discourse that surround a word or passage and can throw light on its meaning. (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/context)

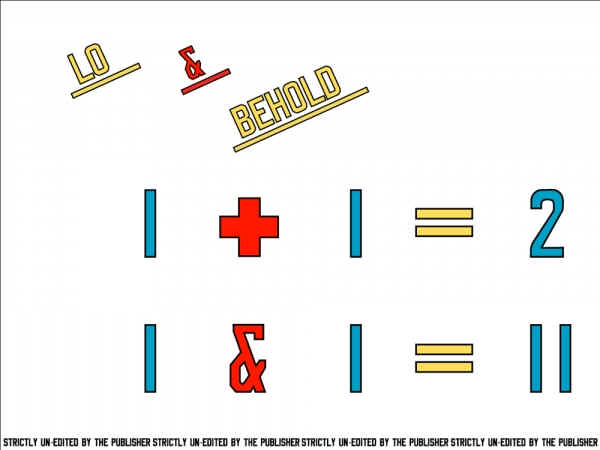

And how about punctuation?

Confession: I am an avid believer in the Oxford comma. It just makes sense (to me anyway)!

Punctuation.

There’s a huge difference in these two statements:

“Let’s eat, Grandma!”

and

“Let’s eat Grandma!”

In addition to (obviously) saving lives, punctuation gives us information about what the sentence means.

Let’s go back to those phrases at the top of the post.

Look at this one: “children should be seen and not heard”. This phrase isn’t used much anymore (thankfully), but was pretty common to hear back in the mid-1900s.

The best I can tell, the origins of this phrase date back to 15th century religious culture, where children, and particularly young women, weren’t allowed to speak unless someone spoke to them directly. It was considered rude and shameful for a child (or female) to speak up.

A clergyman first used this saying in 1450 in a publication called Mirk’s Festial: “Hyt vs old Englysch sawe: A mayde schuld be seen, but not herd.” “Sawe” is an old English word meaning proverb. In Old English, a mayde was a young woman. We aren’t totally sure how the proverb evolved to include ALL children, but we know, based on usage, that it did make that shift. (https://writingexplained.org/idiom-dictionary/children-should-be-seen-and-not-heard_)

If you had no idea about the history of this phrase, and didn’t consider the context in which it was used, you could draw several conclusions as to its meaning:

“Children should be seen and not heard.”

- “Children should be seen”: Children should ALWAYS be in plain sight. The text doesn’t give us permission to let them out of our sight.

- “… and not heard”: Children are not to speak. Again, permission for children to speak is not given, so they must be silent, always and in all places.

- Children should be silent in certain circumstances. I need more information to know which circumstances this applies to.

- Children can do whatever they want – this is a silly old phrase that we don’t take seriously anymore.

Which of those interpretation possibilities you employ depends on a whole bunch of variables, including:

- Knowing who wrote it and what authority they have to tell you (or anyone) what children should do.

- Knowing why it was written.

- Knowing to whom it was written.

- Knowing when it was written (cultural significance).

- Understanding whether it still applies NOW, to your own children.

As you can see, there’s a ton of subjectivity involved in deciding what this fairly simple phrase meant when it was written and what it should mean now.

We might say that sometimes context DOESN’T matter. That some things are just TRUE, forever and always.

But are you sure?

We can say “murder/killing is always wrong”.

How about killing that occurs during war? Or if you are defending your own life? How about the death penalty? Abortion?

All of a sudden, what seemed to be a black and white issue turned very gray.

I know some folks who are OK with some of those scenarios, but not all of them.

And you know as well as I do that there are a variety of opinions about each one of those examples of “killing” – even in the definition of whether or not it IS killing.

Yet most of us would say that it’s wrong to kill.

It sounds like killing should be wrong, right?

And it is.

Except when it isn’t.

Humans are not known for being especially consistent in our logic and reasoning…

It’s important to realize that we can have various interpretations of the same thing, with each person absolutely having good intentions and a well thought-out opinion that makes total sense to that person.

We all have filters through which we process the things we hear, see, and read. Filters include things like our opinions, experiences, education, values and stereotypes. Even things like our mood and our feelings about the author/speaker will impact how we “understand” what is being said.

Most people aren’t aware that they even have filters, let alone that these impact how we interpret the things we read. Understanding your filters, and the filters of others, can help in dealing with the fact that there are many ways to interpret what, at first glance, seems like a straightforward piece of information.

“Children should be seen and not heard.”

Context. It matters. Pretty much all the time.